On August 5th, 2025, delegates from 184 countries reconvened in Geneva at the historical Palais des Nations for a resumed session – INC-5.2 – to negotiate a global plastics treaty. After 10 days of mostly fruitless discussions, the meeting ended without an agreement. There will be no legally binding instrument on plastic pollution for now. What went wrong? And where do we go from here?

Written on site by Felix Nütz

This activity is conducted as part of the Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) under the TwinPolitics project, led by Prof. Alice Vadrot and funded by the European Research Council. In addition to the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations (see Felix’ blog post on INC 5 in Busan here), other venues include the BBNJ Negotiations and those of the International Seabed Authority.

Figure 1: Art installation ‘The Thinker’s Burden’ created by Benjamin Von Wong. Over the course of the week, the statue was increasingly drowned in plastics (Photo: Felix Nütz)

A quick recap: In November 2024, the supposed last session of the International Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a plastics treaty took place in Busan, Republic of Korea. The negotiations were characterized by strong divides between state groups, particularly between the High-Ambition Coalition (HAC) arguing for ambitious measures along the full life cycle of plastics, and the Like-minded Countries (LMC), a coalition of mostly oil-producing states, who favored a treaty focused on waste management and recycling. Therefore, countries could not reach an agreement and decided to adjourn the meeting and continue in 2025. It is now clear that this path did not yield any results – the future of global plastics governance is as uncertain as ever.

Figure 2: Room XX at UN Geneva, with ceiling sculpture by the prominent contemporary Spanish artist Miquel Barceló (Photo: Felix Nütz)

What was the plan here?

Upon arriving in Geneva, I was curious to see how the deep divides that persisted throughout INC-5 and date back at least to INC-3 (Kenya 2023) could be bridged. The meeting’s organisers play an important role here: While the INC Secretariat, established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), is responsible for organising the INC sessions, Luis Vayas, the INC Chair, was elected by members and presides over sessions, guiding negotiations and seeking to facilitate consensus. In his capacity as Chair, Vayas had organized a Head of Delegations meeting in June 2025 at UNEP headquarters in Nairobi to find possible avenues for compromise and discuss work modalities for INC-5.2.

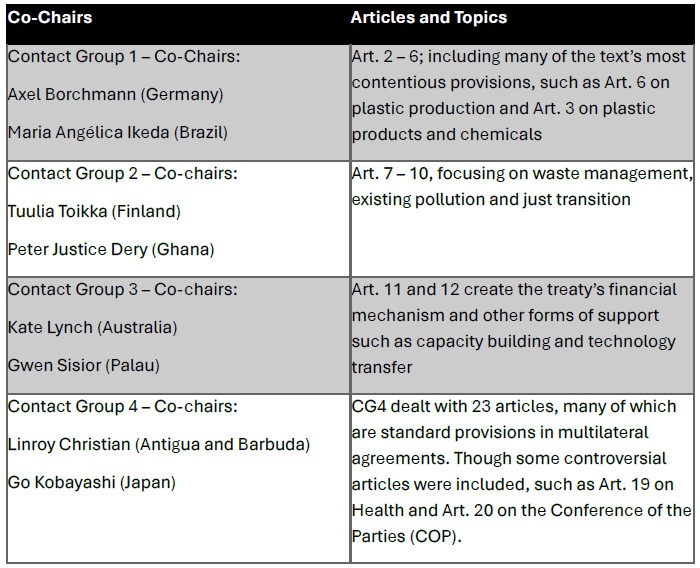

The plan was to start work in Geneva with the relatively streamlined Chair’s text, which was the outcome of INC-5 and contained ‘only’ 372 square brackets, each indicating a contested text option. The text’s 32 articles were divided among four contact groups (CGs) to be individually discussed (see Figure 3). Aware of the significant differences that needed to be overcome, the Secretariat scheduled the Geneva meeting for ten days, each day consisting of nine hours of negotiations.

Figure 3: Overview of Contact Groups at INC-5.2

How the negotiations unfolded

But after a relatively short and productive opening plenary session on August 5th, the negotiations soon returned to a pattern already well known from previous INCs: Endless discussions in the CGs that mostly consisted of stating already well-known positions and debating for hours on end about procedural matters (Cowan et al., 2024; Tiller et al., 2024).

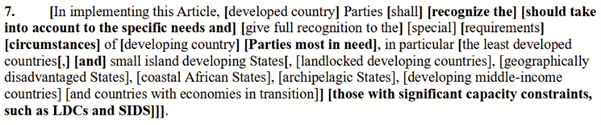

The days started ticking by and the impression grew that even 100 days of negotiations in this format would not have yielded any tangible results. Building on the Chair’s text, members started once again inserting their preferred text options (see e.g. Figure 4). By Saturday 9th of August, when a stocktaking plenary was scheduled, the results from the previous four days of negotiations in CGs were forged together in an Assembled text. To no one’s surprise, the text now contained more than 1.000 brackets and had become completely unreadable (also see Figure 4). Nonetheless, the work in contact groups continued, though now interspersed with informal (‘infs’) and informal informal (‘inf infs’) meetings.

Figure 4: Article 9, paragraph 7, from the Assembled text (August 9) – Everything in brackets

An (un)worthy end to the session

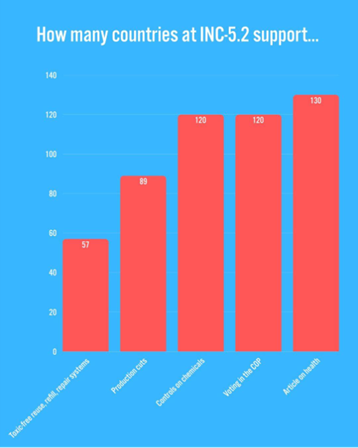

As it was clear that no final text would be agreed on in this work mode, Chair Luis Vayas took over control in the last two days, like he had done in Busan. At this point, many ministers of member states arrived in Geneva for the high-level segment of the session. They participated in informal sessions and were thought to potentially increase the pressure on the negotiations and facilitate a compromise. On August 13 a Chair’s draft text was published, crafted behind closed doors. But this new text sparked outrage among ambitious countries as it excluded many issues advocated by the HAC (see Figure 5):

- The full life cycle approach was not mentioned except for a reference to ‘plastics’ lifecycle’ in the preamble.

- Indigenous knowledge and other knowledge forms were not mentioned at all.

- Article 3 no longer contained measures on identifying and banning toxic chemicals of concern. It further did not contain phase-outs for problematic plastic products such as single-use plastics.

- The entire Article 6 on plastic production was deleted.

- Article 16 no longer contained any mandatory reporting provisions.

- Article 19 on health was deleted entirely.

- Article 20 on the Conference of the Parties only included decision-making by consensus and no voting mechanism.

Figure 5: Numbers of countries supporting ambitious measures. (Source: Environmental Justice Foundation)

For many of the civil society organizations present at INC-5.2 as observers, this proposal confirmed their fears about the prospect of a weak treaty based on the lowest common denominator. Such a treaty could in fact hinder future plastics governance, as it would institutionalize the current unsustainable production model and prevent any future multilateral efforts for ambitious reduction measures.

Ambitious countries reacted very clearly to the new proposal: When Colombia took the floor first in the plenary session convened one hour after the draft’s publication, they received standing ovations for calling the text “completely unacceptable”. Panama doubled down and stated that their red lines had not just been crossed but “stomped, spat on, and burned”. The EU, France, and many others also showed strong opposition and rejected continuing work based on the new text.

This left the Chair with no choice but to prepare a new document in the remaining 24 hours of the session, with the hope that states would agree on this last-minute draft. This seemed highly unlikely. Nonetheless, members made a final push on August 14 in Head of Delegation meetings and regional consultations with the Chair. A plenary session was initially scheduled for 3:30 pm that day but was pushed back 8 (!) times until, finally, at 11:30 pm, the plenary had to convene before the session’s end.

Because deliberations on the new text had not finished and were to continue into the morning hours, the plenary was a short one. In fact, it took exactly 31 seconds (!) for the Chair to tell the plenary to be convened again in the morning when the new text would be completed. For many observers who had been waiting around the venue for 8 hours for this plenary, this statement could only be met with exasperated laughs.

At 6:30 am on Aug 15 it was then clear that these last-ditch efforts proved fruitless and the Chair’s revised text, which had a slightly more balanced approach than the previous version, was rejected in plenary as well. INC-5.2 thus ends without any result. At around 9 am, the session was adjourned to be continued at a later date.

Procedural questions

Of course, the task at hand was a daunting one: How to bring together positions that are so irreconcilably opposed? On the one hand, the ambitious countries, who would like to introduce a global cap on plastic production, phase-out single-use plastics and prohibit toxic plastic chemicals. Among them many countries from the Global South, who carry the brunt of plastic pollution’s adverse effects without having much responsibility for the crisis. On the other hand, the like-minded countries, whose economies depend on oil and plastics and thus oppose any legally binding measures such as production caps or phase-outs. Adding to that the issue of financial support from developed to developing countries presents negotiators with a highly complex situation indeed.

Nevertheless, some questions can be asked of INC Chair Luis Vayas and UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen, who are mainly responsible for overseeing the INC process.

Figure 6: Inger Andersen, Executive Director, UNEP, and INC Chair Luis Vayas, Ecuador. Source: IISD/ENB

For example, important cross-cutting issues were never specifically discussed and thus caused repeated discussions that obstructed work in all CGs. The most important of these issues is the classification of donor and recipient countries, which substantially shapes Article 11 on the financial mechanism and Article 12 on capacity building, but also other articles: Are members separated into developed and developing countries? Do certain groups receive special consideration, most notable least-developed countries (LDCs) and small-island developing states (SIDS), but also land-locked developing countries (LLDCs) or countries with economies in transition? These lists can be continued forever. Instead of settling this issue once and for all in a separate discussion, the job was left to the CGs, which led to the repeated creation of endless enumerations of countries with special needs. Many states argued that this issue should be resolved in a cross-cutting manner — a valid point. However, others continued to insert their preferred text options, on the basis that the issue of special considerations had not been addressed. The question is why the Secretariat had not facilitated a cross-cutting discussion if the demand was so apparent.

Similarly, in the context of a complex treaty with many contentious provisions, it seems evident that a deal incorporating all elements had to be struck. Instead, the key issues were discussed separately in the contact groups until the second-to-last day. This led to avoidable conflicts, where some delegations threatened to stop the work in one contact group if work in another did not progress, or vice versa. In general, low-ambition groups tried stalling progress in specific CGs as much as possible, in particular the oil-producing states in CG1, which dealt with production and plastic products, but also developing countries in CG3 on finance.

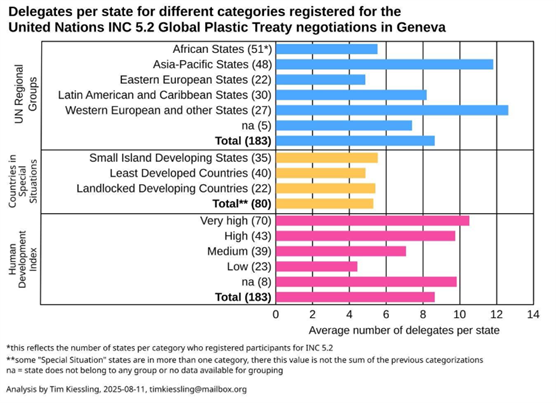

The work mode in parallel CGs and informal meetings – in the last days there were often three meetings happening simultaneously – also put additional pressure on countries with small delegations, especially those in ‘special situations’, such as SIDS and LDCs, and those with a low Human Development Index (see Figure 4).

Figure 7: Analysis of delegates per state, separated in UN groups (Kiessling, 2025)

What’s next – for my doctoral project and the plastics treaty negotiations?

INC-5.2 concluded without a clear way forward. Following its abrupt conclusion at 9 am on 15 August, disappointment prevailed at the fruitlessness of the negotiations and their failure to reach an agreement. The future of the global plastics treaty is therefore very uncertain. Nevertheless, many states committed themselves in their closing statements already to continue discussions, including in the INC setting. This would imply an INC-5.3, for which a date, location and additional funding would first need to be found. These ten days in Geneva have made me doubt whether another session would help to overcome the large divides between HAC and LMC to reach an agreement. If anything, the mode of work would need to be fundamentally reformed, to focus on striking a deal from day one instead of stalling discussions in contact groups for an entire week.

The aim of my research is to explain the contested nature of these negotiations, while continuing to follow the INC process for as long as it takes to reach an agreement. I am especially interested in the politics of knowledge at the negotiations for a global plastics treaty. This includes asking questions such as:

- Does a solid evidence base facilitate consensus among members?

- Can science contribute to breaking the gridlock the negotiations are stuck in, as suggested by Farrelly et al., 2025, among others?

- Which types of knowledge are even considered in the negotiations?

Different forms of knowledge have been constitutive to the current treaty process; be it through scientific research that led to the ‘discovery’ of microplastics in the Ocean and subsequently in our bodies, Indigenous Knowledge on plastics pollution’s detrimental effect on ecosystems or citizen science data to grasp the full extent of marine plastics waste. Moreover, important concepts that are center stage at the negotiations developed from scientific research, such as the full life cycle approach (see UNEP Plastics Science Note), the focus on human health and toxic chemicals (see UNEP Chemicals in Plastics), or the call for production cuts (Bergmann et al., 2022).

If negotiations merely involved translating scientific knowledge into policy, we would probably have reached an agreement by now, given that the scientific evidence is rather clear. However, other factors also need to be taken into account, such as economic interests, geopolitical conflicts and the values each state holds. Economic explanations in particular have been attributed a significant role in shaping countries’ negotiating positions for a plastics treaty (Dauvergne et al., 2025): Oil-producing states oppose production cuts that would negatively impact their petrochemical industry, while developed countries are reluctant to commit to global transfers of finance, technology, and capacity building.

Figure 9: Protest by Greenpeace against the influence of the oil industry at INC-5.2 (Source: Felix Nütz)

For my research, it is then vital to understand how state positions are constructed from an interaction of economic interests, factual knowledge e.g. from science and the norms and values they hold. A basic assumption of my project is that these positions manifest in statements made during the INC, as this is the data I collected through collaborative event ethnography (Vadrot et al., 2025). Using this data, it is possible, for example, to determine whether some countries legitimize their positions more than others with references to science, or to identify key concepts and analyze how they are constructed using scientific knowledge as a basis. A good example of this is the full lifecycle approach with its different interpretations (extraction to disposal favored by HAC vs. design to disposal favored by LMC).

Cooperating with fellow researchers from SINTEF Ocean, we collected around 2.900 observations of statements made during INC-5.2. These cover all the contact group and plenary sessions. As the analysis of the data and preparation of subsequent publications has only just begun now that INC-5.2 ended, stay tuned for more updates and insights in the future!

Sources

Bergmann, M., Almroth, B. C., Brander, S. M., Dey, T., Green, D. S., Gundogdu, S., Krieger, A., Wagner, M., & Walker, T. R. (2022). A global plastic treaty must cap production. Science, 376(6592), 469–470. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq0082

Cowan, E., Tiller, R., & Maes, T. (2024). The Rule of Three: The third session of negotiations (INC-3) on the global treaty to end plastic pollution. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00961-x

Dauvergne, P., Ralston, R., Clapp, J., & Taggart, J. (2025). The petrochemical historical bloc: Exposing the extent and depth of opposition to a high-ambition plastics treaty. Cambridge Prisms: Plastics, 3, e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.10010

Farrelly, T., Brander, S., Thompson, R., & Almroth, B. C. (2025). Independent science key to breaking stalemates in global plastics treaty negotiations. Cambridge Prisms: Plastics, 3, e6. https://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.2

Tiller, R., Cowan, E., Ahlquist, I. H., & Tiller, T. (2024). Standoff at the four-way stop sign: Late-night diplomacy at the fourth session of negotiations (INC-4) on the global treaty to end plastic pollution. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00999-x

Vadrot, A. B. M., Dunshirn, P., Fellinger, S., Langlet, A., Ruiz-Rodríguez, S. C., & Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. (2025). Writing negotiations: Collaborative field note-taking during global environmental meetings. Qualitative Research, 14687941251341984. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941251341984