The first week of the BBNJ Prep-Com in New York had its work cut out for it: How do you form institutions around the benchmark 2023 agreement? And will it be possible to reach the ratification quota of 60 States until the big Ocean conference in Nice, only two months away? This blog post reflects on these discussions and offers initial insights drawn from participant observation by Wenwen Lyu, doctoral researcher in the ERC project TwinPolitics.

Written on site by Wenwen Lyu

This activity is conducted as part of the Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) under the TwinPolitics project, led by Prof. Alice Vadrot and funded by the European Research Council. In addition to BBNJ, other venues include the International Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Treaty and the International Seabed Authority.

A view of the plenary

From 14–25 April 2025, states gathered at UN Headquarter in New York for the first meeting of the Preparatory Commission (Prep Com) under the international agreement on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement).

Nearly two years since the Agreement’s historic adoption in June 2023, 21 states have ratified the agreement, which would be the first of its kind on a global scale . While stakeholders have strongly urged for at least 60 ratifications to enable the Agreement’s entry into force by the UN Ocean Conference in June 2025 in Nice, Prep Com 1 focuses on building consensus around crucial elements of institutional design to support BBNJ’s future implementation. Discussions include the design of key bodies, such as laying out the rules of procedure for the Conference of Parties (COP), Subsidiary Bodies, the Secretariat, and the Clearing-House Mechanism, as well as financial rules and mechanism.

The first week was marked by a positive atmosphere and constructive exchanges among Parties, with emerging convergence on the design of key bodies, alongside a shared recognition of the need for more in-depth analysis of various institutional models. While all formal decisions will ultimately be made by the COP, the current efforts to build consensus are an important step toward advancing the negotiations and ensuring that the institutional architecture is functional from the outset of the COP.

Shaping the rules of procedure of the COP

Following the adoption of the agenda, the first day discussion focused on the rules of procedure of the COP, the governing body of the BBNJ. Applying the note-taking method of the MARIPOLDATA project (Vadrot et al. 2024, Vadrot et al. forthcoming), I systematically captured Party interventions on each section and rule outlined in the Aid to Discussion document on the rules of procedure of the COP (A/AC.296/2025/3) prepared by the co-chairs of Prep Com. This approach provided an overview of the key issues raised during the discussion.

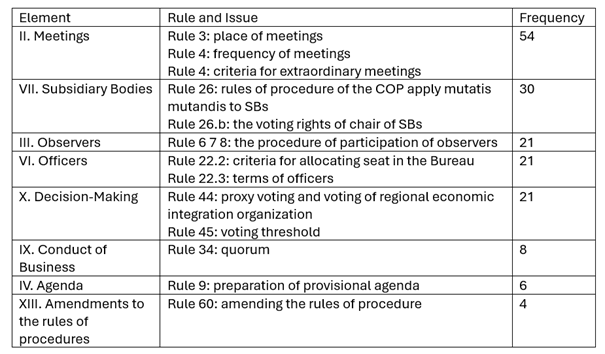

Figure 1: The frequency of interventions on the rules of procedure of the COP during the Prep Com1

Based on all interventions on Monday, the co-chairs compiled a non-exhaustive list of discussion points for Wednesday. Diverging rationales emerged regarding the frequency and location of COP meetings. While rotating the host country was seen as a way to enhance inclusive participation and equitable representation, some Parties raised concerns about the associated costs, highlighting the intricacy of balancing cost-efficiency with broad representation. There was broad agreement on holding annual CoP meetings at the beginning to manage the heavy workload and establish a strong institutional foundation, followed by a transition to a biennial format. However, opinions varied on how to reflect this in the text. For instance, whether to set a one- or two-year default, and whether to include a time limit for transitioning. Other extensively discussed topics included meeting formats, observer participation, voting threshold and criteria for extraordinary meetings, and emergency measures.

Overall, the first week discussions on rules of procedure of the COP reflected a collaborative spirit and a willingness to engage constructively, with states actively responding to one another’s proposals and perspectives. The detailed deliberations highlighted Parties’ caution in shaping the BBNJ Agreement’s governing body and their shared commitment to establishing a robust COP that can support a comprehensive and universal regime for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Looking ahead, more divergent views can be expected for the second week as inherently political issues related to decision-making are on the agenda. These include voting rights for the chair of subsidiary bodies, voting of regional economic integration organizations, whether regional economic integration organization shall exercise its right to vote with a number of votes equal to the number of its member States that are Parties to the Agreement when none of its member States exercise rights to vote (proxy voting), and quorum.

Secretariat: Stand-alone or link to the UN?

Another crucial institutional arrangement under discussion is the Secretariat. In the document prepared by the interim Secretariat, the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS) (A/AC.296/2025/5), two possible models are outlined as background information for Parties’ consideration. The first is a stand-alone model, exemplified by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which would allow the BBNJ Secretariat to operate independently. The second model envisions an institutional linkage with the existing UN system while maintaining a degree of autonomy, with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) frequently cited as an example.

Several Parties, such as the African Group, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), Pacific small island developing states (P-SIDS), noted that a linkage to the UN system could help avoid starting from scratch and reduce financial and administrative burdens. Others, such as China and the Philippines, pointed to a stand-alone model to better serve the objectives of the BBNJ Agreement. As the Core Latin American Group (CLAM) emphasized, “the size and financing of the Secretariat will be directly determined by its relationship with the United Nations system.” In light of these perspectives, Parties remained cautious and open, agreeing to prepare a comparative analysis of the secretariats under existing multilateral environmental agreements. This analysis will consider key elements such as legal personality, privileges and immunities of the Secretariat and its staff, and, importantly, the financial implications of each option.

Belgium and Chile have both expressed interest in hosting the Secretariat—a friendly competition humorously described by the Micronesian delegate as “Belgian Beer vs. Chilean Wine.” While some states proposed that the Preparatory Commission set clear criteria for selecting the Secretariat’s seat, others cautioned against micromanagement, suggesting instead that both countries be invited to submit their own proposals.

Belgium’s pitch for hosting the BBNJ secretariat in Brussels.

Discussions on the Secretariat also underscored its interlinkages with other institutional arrangements under the BBNJ Agreement. The Secretariat shall manage the Clearing-House Mechanism, and the chosen model will determine the financial model to be adopted. Moving forward, Parties agreed to begin preparing a draft for text-based negotiation at Prep Com 2, which, according to the co-chairs, will be informed by next week’s discussions and include all Secretariat models supported by different states.

What Parties Expect from the Subsidiary Bodies

Parties were invited to share their general considerations regarding the rules of procedure, functions, modalities, and membership of the Subsidiary Bodies (SBs), as outlined in document A/AC.296/2025/4. This general exchange was intended to precede more detailed, case-by-case discussions of the five SBs: the Access and Benefit-Sharing Committee, Capacity-Building and Transfer of Marine Technology Committee, Finance Committee, Implementation and Compliance Committee, and the Scientific and Technical Body (STB).

There was broad convergence on applying the rules of procedure of the COP mutatis mutandis to the SBs, while recognizing the need to reflect the distinct roles and mandates of each body, either within a single document or through separate documents for each body. Many Parties emphasized that all SBs should be fully operational by COP1 to ensure effective implementation of the BBNJ Agreement. Figure 2 depicts a cloud generated from Parties’ statements (on discussions on subsidiary bodies) to illustrate recurring expectations.

Figure 2: Top Mentioned Features of Subsidiary Bodies

Parties proposed limiting the number of members in each SB to strike a balance between efficiency and representation. The G77 and China, Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), and PSIDS underscored the need to ensure seats for developing countries and special groups. Parties also stressed equitable geographical representation and gender balance in line with treaty language. Other expectations included ensuring transparency through observer participation and increasing inclusivity by involving early-career professionals.

A new proposal was put forward by the PSIDS for the establishment of an overarching Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) advisory group, composed of self-selected members from seven socio-cultural regions1 to support the SBs by integrating traditional knowledge and ensuring inclusive representation. The United Kingdom expressed interest in the proposal, pending further details, which PSIDS intends to elaborate at Prep Com 2.

Several proposals were made to safeguard the independence and technical nature of SBs. These included: drawing on external expertise; enabling SBs to determine their own work programmes, meeting formats, and frequencies; and appointing members who serve in their individual capacities; facilitating coordination with the COP and the Clearing-House Mechanism; allowing SBs to interact directly with one another without going through the COP; encouraging cooperation with SBs under other international frameworks. Regarding the last point, the Colombian delegate noted that it may not be possible to ensure that SBs under other frameworks have the mandate to engage directly with BBNJ SBs without going through their own COPs. Many Parties considered this an important issue and agreed that, at the very least, SBs under the BBNJ Agreement should be granted the mandate to cooperate with counterparts in other frameworks, highlighting this as a key area for further exploration.

Scientific and Technical Body: Informing Design Through Agreed Functions

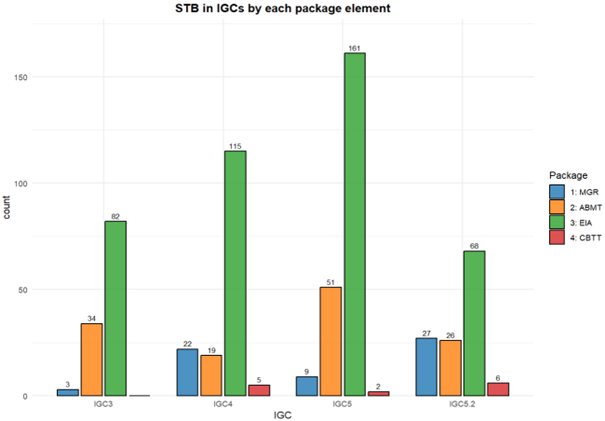

Regarding the Scientific and Technical Body (STB), several Parties emphasized that its functions, which have already been set out in the BBNJ Agreement, should guide its formation. The Colombian delegate, speaking on behalf of the CLAM, summarized the STB’s functions under the Agreement, which are primarily focused on Areas-Based Management Tools (ABMTs) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Following a similar logic, the European Union also stressed the STB’s role in ABMTs and EIA. China proposed the establishment of two separate working groups, one for ABMTs and the other for EIA.

At the same time, broader expectations for the STB were also raised. The Philippines, for instance, noted the STB’s relevance to benefit-sharing of Marine Genetic Resources (MGR), while Canada cautioned against limiting the eligibility criteria for STB membership solely to ABMT and EIA expertise. These views reflect the cross-cutting nature of scientific and technical inputs across the Agreement’s four package elements. Although the final BBNJ text refers to the STB only in the context of ABMTs and EIA, discussions from IGC 3 to IGC 5.3, as captured in the MARIPOLDATAbase, show that Parties frequently considered the STB in the context of other elements as well. This history of negotiation helps explain why some Parties see value in STB’s potential to support a wider range of functions and to coordinate closely with other institutional bodies under the Agreement (regarding multiple ways to use MARIPOLDATAbase, see MARIPOLDATA blog post by Langlet and Vadrot).

Figure 3: The discussions on STB in each IGC by Package

Moreover, similar to expectations for other Subsidiary Bodies, the STB is also expected to be as independent, transparent, science-based, and inclusive as possible, with some Parties emphasizing the importance of ensuring that minority views are reflected in its membership composition, reporting, and recommendations.

While recent research has highlighted potential tensions and trade-offs between the Scientific and Technical Body’s (STB) influence and the risk of politicization (Gaebel et al., 2024) , such concerns have not yet surfaced in Parties’ initial interventions. Discussions on the STB are expected to continue in the second week, with Parties likely to explore its functions and composition in greater depth.

High hopes with a tiny grain of sea salt

Establishing strong institutions is essential to ensure the effective implementation of the BBNJ Agreement. The first week of discussions on institutional design marked a promising step toward this ambitious goal. Yet, this is only one side of the story. Equally significant is the ratification process, which will determine whether the treaty can become fully operational. Despite the aspiration for universality, concerns have been raised about the uncertainty surrounding how many Parties will have ratified the agreement by COP 1. Although neither expected nor desired, the possibility that only a relatively small number may be present raises concerns about the legitimacy of early decisions. For instance, can sixty Parties legitimately make foundational choices on behalf of all future members? This uncertainty has tempered the momentum for the rapid adoption of decisions, including the establishment of strong institutions from the outset.

In the second week, discussions on institutional arrangements are expected to deepen, alongside negotiations on financial rules, funding mechanisms, and the Clearing-House Mechanism. These conversations will be pivotal in shaping how the agreement transitions from words on paper to meaningful action.

Stay tuned for more updates as we follow this historic process.