The Fifth session of the International Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, ended on an emotional note without agreement but with hopes of a treaty in 2025.

Delegates from more than 180 countries gathered in Busan, Republic of Korea, between 25 November and 1 December 2024. Observers and scientists from all over the world hoped that they would address a key menace to the Ocean and deliver an ambitious global plastics treaty. After seven days of intense negotiations and a closing plenary that lasted until 3am on Monday 2 December, however, it became clear that governments failed to deliver: no agreement was reached in Busan and the International Negotiating Committee (INC) will have to reconvene for a resumed session, presumably in the first half of 2025, with the exact date and location to be determined.

Written on site by Felix Nütz

I followed the negotiations as observer and doctoral researcher for the TwinPolitics research project (University of Vienna), funded by the European Research Council and led by Associate Professor Alice Vadrot. I explored the site of the plastics negotiations and gained insights into key conflicts as well as the relevance of data and emerging technologies for a global plastics treaty. In this blog, I discuss the negotiation format and atmosphere and analyze the scope of the treaty.

Felix Nütz, TwinPolitics

INC-5: High expectations, mixed with strong doubts about the outcome

In the run-up to INC-5, conflicting emotions prevailed among delegations and observer organizations alike. On the one hand, the pressure to produce an effective treaty was mounting in the light of the (supposedly) last INC session. On the other hand, it was completely unclear how to overcome the sharply divergent positions of ambitious and less ambitious country groups. It was in this context that INC-Chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso from Ecuador introduced the third iteration of his non-paper in October, result of intersessional work that had been carried out with Heads of Delegations in August of this year in Bangkok. Moreover, the Chair proposed that the work in Busan be carried out in four contact groups, each dealing with different articles of the draft text. The key question, however, was: How would Parties react when the Chair introduces the proposed work mode under agenda item 3.C in the opening plenary?

And indeed, the opening session of INC-5 on 25 November dragged on for 3 hours longer than planned, heated discussions on the mode of work included. Many countries supported the process proposed by the Chair, most notably those organized in the important High-Ambition Coalition (HAC). The HAC, founded by Rwanda and Norway in 2022, has 68 official members as of today, though for some issues the number of ambitious countries goes up to 100. Strong opposition came from two other country groups that would stay present throughout the week: the group of Like-Minded Countries (LMC), including Russia, Saudi Arabia and China, as well as the Arab Group, led by the omnipresent delegation of Saudi Arabia. The groups’ opposition succeeded to the extent that the Chair had to clarify that the compilation text, the dreaded 73-page outcome of INC-4, was to be considered an authoritative reference alongside the non-paper. Nonetheless, work in contact groups commenced in the evening of INC-5’s first day.

Observers from Indigenous organizations stand up with raised fists in plenary on Wednesday 27 November

Adding to the tense atmosphere, observers from Indigenous organizations stood up during a plenary session, raising their fists and shouting to demand the right to speak. With the meeting already running overtime, the Chair the Chair initially resisted but relented after Tuvalu’s delegate urged him “to let the Indigenous People speak.” The statement emphasized their status as rights holders, not just knowledge holders, and highlighted the disproportionate impact of plastic pollution on Indigenous Peoples and their lands. The statement was greeted with loud applause. Some observers said that this clear defiance of the rules of diplomacy by Indigenous Peoples was a moment unseen in recent decades of multilateral negotiations, underscoring their frustration at being excluded from the process.

Contact Groups

The meetings in contact groups on the first days brought their own challenges: With up to three contact groups convening simultaneously, the strain on small negotiations in particular was enormous. It was also impossible for me, as a single researcher, to follow all contact groups. I therefore concentrated my efforts on Contact Group 4, which focused on monitoring, research, and information exchange, and Contact Group 3, which dealt with finance and capacity building.

Perspectives of observers on Contact Group 4

Worryingly, work in the contact groups was extremely slow and fraught with discussions on procedure. Countries from the previously mentioned groups continuously questioned the relevance of the non-paper and introduced lots of additional text, leading other delegations to fear so-called “line-by-line” negotiations. Even in less contentious articles, some single paragraphs were discussed for up to three hours, ballooning from four lines to 20.

Nevertheless, the contact groups served the purpose of identifying areas of convergence – or rather less divergence – as well as contentious topics that would require special attention in order to reach an agreement later in the week. The two main lines of conflict, which existed before the INC-5 meeting but became more apparent in Busan, revolved around the scope of the treaty and the financial mechanism.

Scope of the Treaty

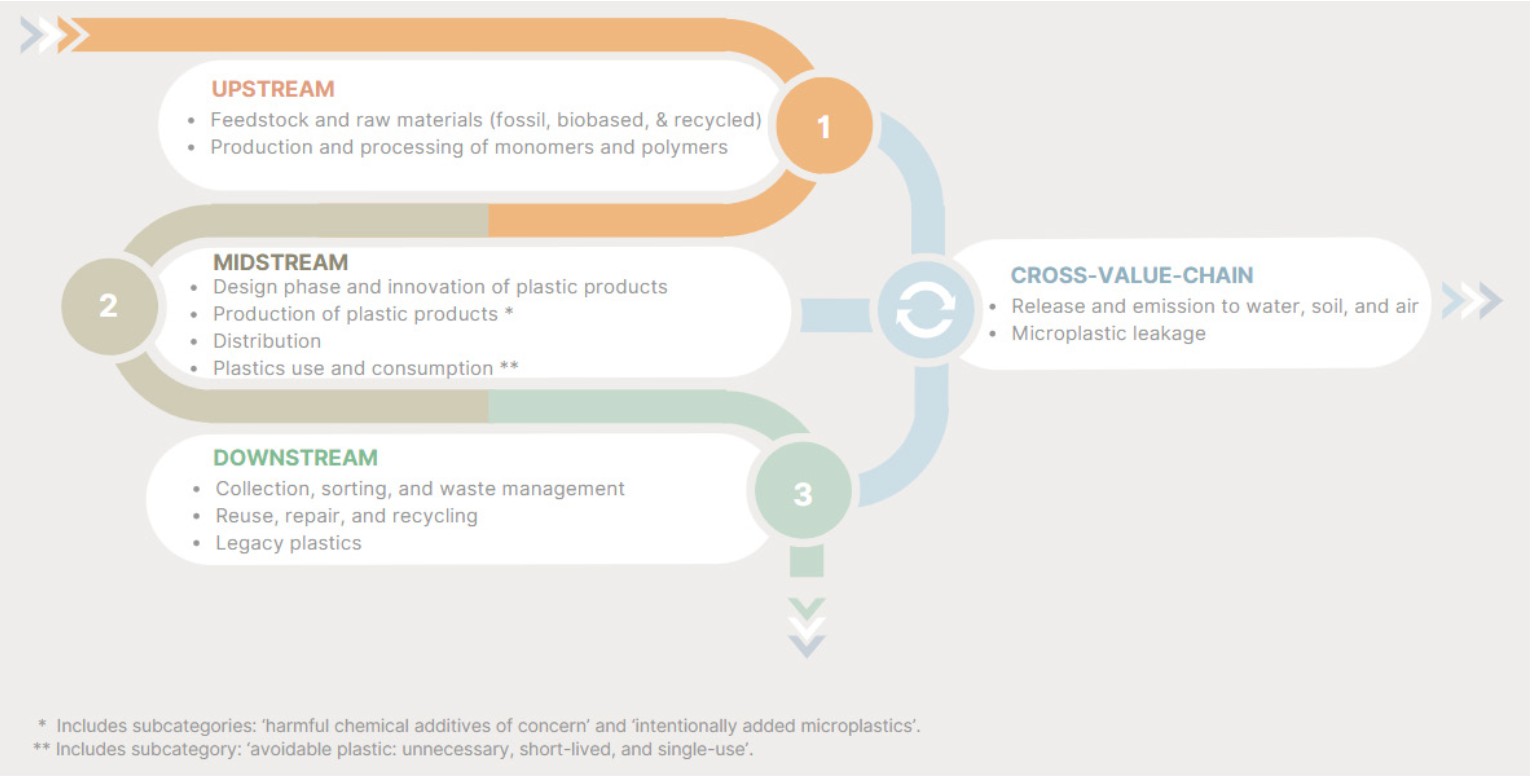

The most important discussion in the plastics negotiations concerns the question of which topics should even be included in the new treaty. This was most palpable in negotiations on a standalone article on scope, article 3 on problematic plastic products, and article 6 on supply. The LMC and Arab Group favored a limited scope of the treaty, focusing on downstream measures like improved waste management or recycling (see Figure 1 for an explanation of up-, mid- and downstream measures). The Russian Federation, for example, introduced a scope provision that explicitly excludes the supply of polymers, the basis for all plastic products, from the scope. Other LMCs repeatedly highlighted that the aim of the instrument was to end plastic pollution and not to end plastics, and that excessive measures against plastic production would cause economic damage to developing countries especially.

Figure 1 illustrates the lifecycle stages of plastics, which are key to the scope debate

Member of the HAC – most notably Rwanda, Panama, Mexico, Fiji as well as the EU – instead called for the inclusion of up- and midstream measures, like caps on plastic production, the removal of toxic chemicals or the phase-out of high-leakage plastic products. The HAC argued that the treaty’s scope is already set out in UNEA resolution 5/14 which started the INC-process in 2022. Countries in this resolution opted for the wording “based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastic” (p. 2, highlighted by author). Delegates from this group argued that the goal of ending plastic pollution is not reachable without reducing plastic production, which is set to triple by 2060 (Our World in Data, 2024). Additionally, the circular economy – a key concept in the negotiations – cannot be implemented if toxic chemicals are present in plastic products, or if single-use plastics remain prevalent. The LMC on the other hand argued that provisions on supply and chemicals were not within the UNEA mandate and should be covered by other conventions, like the Basel, Rotterdam or Stockholm conventions on hazardous chemicals and transboundary waste trade.

The outcome of the meeting, a fifth non-paper circulated on Sunday 1 December, did not include a stand-alone article on scope, but also did not mention chemicals of concern. The annex to the paper did include a specific list of single-use plastic products to be phased out by a specific date in the 2030s. Article 6 on supply remained heavily bracketed, with a zero option to delete the article altogether.

A standalone financial mechanism to combat plastic pollution?

Financing is known to be a contentious issue in any multilateral agreement. This is also the case for the potential plastics treaty. For this reason, the Chair’s non-paper in October did not include any text for Article 11, instead encouraging Parties to submit their texts during the Contact Group meetings. This approach worked reasonably well at first, as only two major proposals were submitted, one by the United States on behalf of other developed countries, and one by Ghana on behalf of the African Group, GRULAC and other developing countries. The key conflict arose when defining donor and recipient countries, as well as discussing the establishment of a standalone fund for the implementation of the treaty. For the definitions, wording proved to be very important, with the Ghana proposal favouring wording that explicitly asks for support by developed country Parties for developing country Parties, especially least-developed countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) etc. The US proposal, on the other hand, sought to overcome the dichotomy of developed and developing countries, favouring wording that Parties “with both the financial capacity to do so and with high levels of plastic leakage, plastic product production, or polymer production” (US, 2024) should provide support on a voluntary basis through the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) for “Parties most in need” (ibid.). This approach was strongly criticized in the contact groups by developing countries, arguing that developing countries were played off against each other and that the historical responsibility of developed countries was ignored. Moreover, they noted that the GEF does not provide sufficient resources to recipient countries.

Side Events

Being present at multilateral negotiation sites is not only an opportunity to observe negotiations between state delegations, but also to hear other organizations’ perspectives in side events. As the role of data and digital technology did not play a major role in the actual negotiations but is a key interest of the TwinPolitics research project, I sought to hear more on the topic at relevant side events. Interesting examples were two side events organized by the University of South Wales’ Centre for Sustainable Development Reform on the development of national data systems, and an event organized by Our Sea East Asia Network (OSEAN) on citizen science in the global plastics treaty.

Side Event: Developing national data systems to drive decision-making for the global plastic treaty and beyond

These events showed that there are many organizations globally focusing on collecting data on plastic pollution, its hotspots, and influxes. Noting the challenges these organizations face, as well as their hopes for a global plastics treaty, showed me that the availability and accessibility of data on plastic pollution and its environmental impacts will play an important role in forming and implementing a successful treaty. While there are many interesting initiatives, such as OSEAN using AI and citizen science to map and model types of plastic waste and its hotspots, an infrastructure to collect and integrate this data at the national level, let alone the international level, is lacking. Providing data from civil society and government organizations is so important because data from companies in the plastics industry has proven unreliable in the past, many participants highlighted.

Outlook and conclusions

Towards the middle of the week, the Chair decided to change the format of consultations from contact groups to closed sessions between member delegations, thereby denying access to observers such as myself. By limiting transparency, the Chair hoped for a more open discussion that could produce tangible results by the end of the week, even if the goal of agreeing on a treaty in Busan would be missed. On the session’s last day, the secretariat released the fifth iteration of the non-paper, a so-called Chair’s Text, which was the result of the closed meetings with Heads of Delegations. Though the text had been streamlined and many disagreements resolved, the more contentious articles outlined above remained riddled with brackets. It remains to be seen how these issues can be overcome to reach an agreement at INC 5.2 (date and place to be determined).

Ambitious countries could gather momentum on the final day of the session, organizing a joint statement in a delegate-packed press room to show strength and unity. In the closing plenary, the coalition also delivered some strong statements, for example Rwanda on behalf of all high-ambition countries, urging the delegates to rise for ambition (video). Also notable were the statements made by Panama (video) and Mexico on behalf of 95 countries to include chemicals in the treaty, naming all countries in her statement to applause from the room.

Mexico, delivering their statement on behalf of 95 countries in the closing plenary on 1st December.

However, the Head of Delegation from Saudi Arabia was quick to remind the committee that the LMC still represented more than half of the world’s population, and their opposition remained strong. Even though some delegates toyed with the idea of pushing through an ambitious treaty without the consent of the LMCs, most agreed that the involvement of all countries, especially major oil and plastic producers, was necessary to achieve the goal of ending plastic pollution. Therefore, in the early hours of Monday 2 December, the committee agreed to meet in the same format in early to mid-2025 and continue negotiations on the basis of the Chair’s Text, in the hope that differences on the key issues could be resolved then.

Sources

Dreyer, E., Hansen, T., Holmberg, K., Olsen, T., & Stripple, J. (2024). Towards a Global Plastics Treaty: Tracing the UN Negotiations. Lund University.

Our World in Data (2024). Plastic Pollution. https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution.

UNEP. Environment Assembly (5th session 2021). 5/14. End plastic pollution: towards an international legally binding instrument. Resolution / adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3999257/files/UNEP_EA.5_RES.14-EN.pdf?ln=en

United States of America (2024). Text proposal for Article 11: Financial Resources and Mechanism. https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/text_proposal_art11_financial_resources_us_aus_nor_che_jpn_uk_nz_rok_can_ice_eu_1_0.pdf