Held in Nice, France, from 6–13 June 2025, the 3rd UN Ocean Conference (UNOC3) provided a unique platform to explore the intersection of digital twins and ocean governance. As a doctoral student in the TwinPolitics research project led by Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alice Vadrot, my work focuses on the political dimensions of digital twins. This conference offered an invaluable opportunity to gather data for my research and the TwinPolitics project. Together with my colleague Hristina Talkova, I employed a hybrid ethnographic approach to systematically document the social and technical components, as well as the imaginaries surrounding the European Digital Twin of the Ocean (EU DTO), primarily at the European Digital Ocean Pavilion and at selected UNOC3 side events.

Written on site by Carolin Hirt

This activity is conducted as part of the Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) under the TwinPolitics project, led by Prof. Alice Vadrot and funded by the European Research Council. In addition to UNOC3 (see a blog post on the results of UNOC3 here), other venues include the International Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Treaty and the International Seabed Authority.

Figure 1: The entrance of the “Whale” (source: Carolin Hirt)

The Whale

The European Digital Ocean Pavilion, nicknamed La Baleine (the ‘Whale’) and located in the Green Zone of UNOC3, was designed as an immersive installation evoking the experience of entering a whale. Blending elements of an expo, a scientific conference, political ‘theatre’, and an entertainment venue, this space hosted pavilions from various organisations, auditoria, and spaces for meetings and consultations. As it was open to the public and free to access, it created an environment in which school groups, industry representatives, NGOs, scientists, politicians, and citizens could interact.

Figure 2: The area right after the entrance of the “Whale” (source: Carolin Hirt)

Figure 3: Inside the “Whale” (source: Carolin Hirt)

The European Digital Ocean Pavilion and the EU DTO

The European Digital Ocean Pavilion was coordinated by Mercator Ocean International (MOi) on behalf of the European Commission’s Directorates-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS), Research and Innovation (DG RTD), Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE) and International Partnerships (DG INTPA).

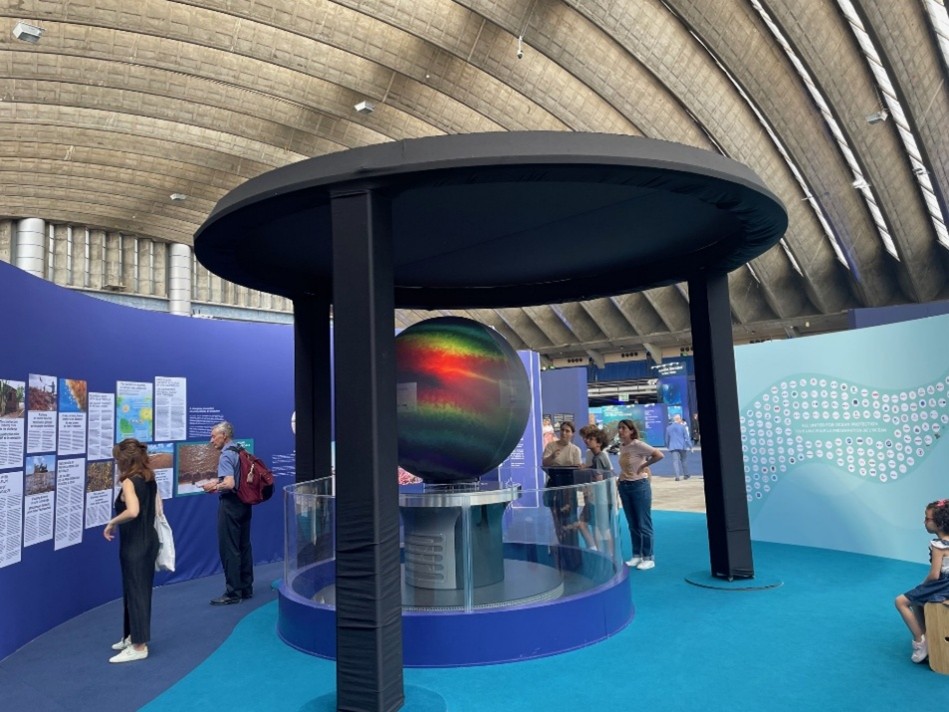

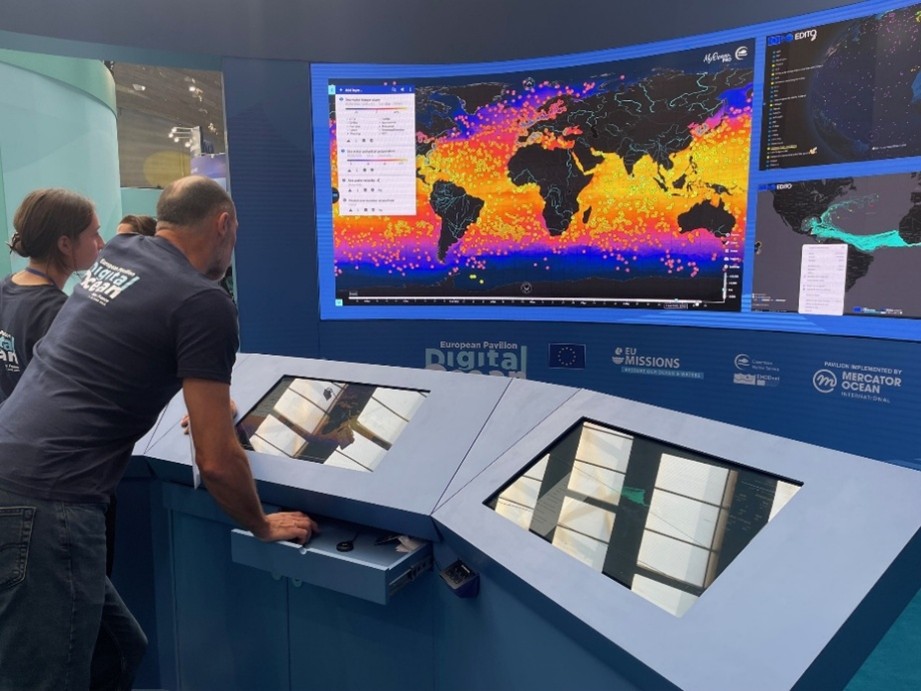

The European Digital Ocean Pavilion was divided into three distinct areas: ‘engage’, ‘inspire’ and ‘decide’. The ‘engage’ area functioned as an exhibition featuring 3D visualisations of the globe, data collection instruments, and other interactive displays (see figure 4). The ‘decide’ area resembled a control center where visitors could explore a demo version of the EU DTO on a large screen and test its applications with the help of on-site technical staff (see figure 5). The ‘inspire’ area, the focal point of my fieldwork, hosted live events such as talks and plenaries. These sessions addressed topics related to ocean digitalisation, including citizen science, in situ and satellite ocean monitoring, forecasting models and key ocean challenges such as biodiversity, pollution and climate change. EU-specific topics were also featured, including Copernicus, the Earth observation component of the EU space programme, and the EU Ocean Pact, launched during UNOC3.

In general, the European Digital Ocean Pavilion showcased the EU’s approach to ocean science, with a particular focus on the EU DTO: first announced by the European Commission under the EU’s “Mission Restore our Oceans and Waters” in February 2022. The EU DTO is defined as “an interactive replica of the ocean for better decision-making.” (European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. 20221) It is described as a digital space that draws on existing ocean data infrastructures—such as the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet)—and integrates vast amounts of marine and satellite data, advanced models, artificial intelligence, and citizen science to replicate the properties and behaviors of marine systems. While not fully operational yet, a key application of the EU DTO is to enable analysis of what-if scenarios, allowing researchers, citizens, and local authorities to assess the effectiveness of potential future policies (EC 2025a). For example, one application simulates how seagrass reduces coastal erosion, helping policymakers compare nature-based and technological solutions. Another models global plastic drift to evaluate how emission cuts affect local plastic pollution (MOi 2025).

The demo version of the EU DTO was publicly unveiled for the first time at the European Digital Ocean Pavilion, where Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, experiencing the EU DTO first-hand and underscored its importance (see figure 6).

Figure 4: The “engage” area at the European Digital Ocean Pavilion (source: Carolin Hirt)

Figure 5: The “decide” area at the European Digital Ocean Pavillon (source: Carolin Hirt)

Figure 6: Von der Leyen experiencing the EU DTO (source: Linkedin “Mission Ocean”)

The EU Ocean Pact: Positioning the EU as leader in marine science and technology

The EU Ocean Pact was presented by von der Leyen as the “European vision of ocean governance”: a strategy and reference framework designed to promote the Blue Economy, protect the ocean, support coastal communities, advance ocean research, and strengthen international ocean governance and EU ocean diplomacy. This approach aims to bring coherence to the EU’s marine policies and comes with a budget of €1 billion. To achieve the Ocean Pact’s targets, the Commission announced it will propose an Ocean Act by 2027. The Act is intended to establish a single framework to implement the Pact’s objectives (EC 2025b). While this ambition is important for ocean protection, several NGOs—including BirdLife Europe, ClientEarth, Oceana, Seas At Risk, Surfrider Foundation Europe, and WWF—criticised the Pact for lacking concrete, legally binding measures to tackle harmful activities such as overfishing, pollution, and destructive practices in protected areas (WWF 2025).

Within the EU Ocean Pact, about one third of the budget will be allocated to ocean science and research (Portala 2025). Against a backdrop of uncertainty and funding cuts for ocean observation in the United States, as well as broader geopolitical shifts, the EU aims to strengthen its autonomy in information, data services, and critical ocean infrastructure, while continuing to promote international scientific cooperation (EC 2025c: 14). As the Commission notes, “The Ocean Pact proposes to step up European efforts by launching an ambitious ocean observation initiative, including for the coastal and deep sea, covering the entire knowledge value chain, and taking a leading international role, to deliver critical information to all marine actors and sectors” (EC 2025c: 14).

This EU Ocean Observing Initiative is closely connected to the EU DTO: the data and infrastructure it generates will feed directly into the EU DTO, which plays a central role in the Pact by supporting “evidence-based policymaking” (EC 2025c: 15). The objective of the EU DTO therefore is to provide policymakers with tools grounded in data and science, promoting the idea of an apolitical, objective approach to decision-making. However, while technological developments like DTOs are essential for advancing ocean science and governance, they are themselves inherently political, as science, technology, and data are never entirely neutral.

Immersing in hybrid ethnography

The ‘inspire’ area offered a structured setting to explore both the social and technical dimensions of the EU DTO, as well as the imaginaries surrounding digital twins—a central focus of my PhD research. Identifying these technical and social components is essential for understanding the EU DTO as a socio-technical network that does not arise in a vacuum. At the same time, examining the sociotechnical imaginaries of the EU DTO provides a lens to analyse how ideas and visions about digital twins make the ocean legible and governable. Sociotechnical imaginaries can be described as collectively held visions of desirable futures that both shape and are shaped by the development of science and technology (Jasanoff & Kim 2015). They are not only descriptive but also performative, materialising, for example, in specific policy choices or decisions about ocean data collection foci. As the Digital Ocean Pavilion was hosted by the European Commission, the events in the ‘inspire’ area provided an ideal setting for data collection. All activities were connected to the EU DTO in some way, from presentations by scientific experts on data collection methods and programmes (e.g. in situ monitoring, satellite observations and citizen science) to talks by leading figures from key institutions, such as EDITO — which is currently building the EU DTO — and employees of the European Commission itself.

The fieldwork unfolded in two phases. During the first week, I conducted digital ethnography, attending sessions virtually and taking systematic field notes using an adapted version of the matrix developed by Vadrot et al. (2025). This phase enabled me to refine my methods and prepare for the dynamic environment of the second week, during which I adopted a hybrid approach. Combining on-site participation (see figure 7) with ongoing digital support from my colleague Hristina Talkova in Vienna allowed me to fully engage with the conference atmosphere while ensuring that I did not miss anything: while the lively atmosphere of the Green Zone was inspiring, it posed difficulties for systematic note-taking due to the high levels of noise and activity. To address this, Hristina and I organised our schedules accordingly to maintain focus and ensure the quality of our observations. Despite these challenges, the conference was a pivotal moment for my research, offering a unique opportunity to explore the social and technical components of the EU DTO and imaginaries of DTOs. In general, conducting fieldwork at UNOC3 was both rewarding and challenging.

Figure 7: How the field-note taking looked like (source: Carolin Hirt)

The Preliminary Findings: Transformative technology with surprising gaps

The fieldwork produced a wealth of data, and the initial findings suggest that DTOs, particularly the EU DTO, are conceived in both broad and specific terms.

The broad vision portrays DTOs as tools that support ocean governance through science, connect society with the ocean and enable new research approaches. They are also described as instruments of learning that enable users to ‘go back in time’, offering insights that can inform better policy decisions. Often described as transformative technologies, DTOs are considered essential for addressing global challenges and ensuring a sustainable future for life on Earth. While these visions align with the general objectives of DTOs, they often remain abstract, reflecting a generic understanding of their role in ocean governance. Notably, there are narratives that emphasise the potential of DTOs to bring society closer to the ocean, highlighting a performative vision in which DTOs reshape the human–ocean relationship. This supports the idea of DTOs as transformative technologies. More specific examples include using DTOs to combat illegal fishing, providing universal access to ocean data and advanced models, and integrating disparate datasets into a unified global network. The vision focusing on illegal fishing, for example, may hint at future policy priorities. However, these are just preliminary findings; a more detailed analysis of the sociotechnical imaginaries surrounding DTOs is currently underway.

The fieldwork also revealed some surprising gaps. Despite the prominence of the EU DTO, there was a notable absence of critical discussion about its political dimensions. One of the few critical perspectives that have emerged suggests that the concept of a digital twin is underdeveloped. This emphasises the need for ‘high-quality’ research conducted by locals, and notes that this technology is currently far from achieving its ambitious goals. At the side event organised by our team (report to come), critical views were also expressed, questioning the vast amount of money invested in this tool and raising concerns about data trust and legitimacy. The event also saw criticism of the hegemonic nature of the EU DTO from the perspective of Small Island Developing States.

However, the majority of presentations and panel discussions at the Digital Ocean Pavilion focused on the technical capabilities and potential benefits of the EU DTO, paying little attention to the challenges or political implications it entails. As the pavilion was organised by the European Commission, this is perhaps unsurprising. Nevertheless, this absence underscores the importance of my research in highlighting the political dimensions of digital twins.

As I analyse the collected data, I look forward to contributing to academic and policy debates on the potential influence of digital twins on the future of ocean governance, and on our understanding of digital twins as socio-technical relations that do not arise in isolation. UNOC3 deepened my understanding of the EU DTO and emphasised the increasing significance of digital technologies in ocean governance. This fieldwork marks an important step in my research journey, and I look forward to sharing my findings in future publications.

Carolin Hirt is a doctoral student in Political Science at the University of Vienna and a researcher with the TwinPolitics project. Her work focuses on the political dimensions of digital twins in ocean governance and the making-of the EU DTO.

1 European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. 2022. The Digital Twin Ocean: An Interactive Replica of the Ocean for Better Decision Making. LU: Publications Office.

Find Arne Langlet’s blog on our activities at UNOC 2025 here: Ocean Governance at a critical juncture ahead of the Third UN Ocean Conference 2025 – our participation at UNOC 2025 – Twin Politics

Find Paul Dunshirn’s blog on the results of UNOC 2025 here: Environmental science and diplomacy at stake at the 3rd UN Oceans Conference – Twin Politics

Find our Ocean Data Survey here: Ocean Data Survey – Twin Politics

Find other blogs on conference participation here: Blog – Twin Politics

[auf Deutsch] Unser Presse-Echo zur UNOC 2025 finden Sie hier:

- War die UN-Ozeankonferenz in Nizza für die Fisch’? im Standard am 14.06.2025

- Meeresdiplomatie: Warum ist es so schwierig, sich auf Strategien zum Meeresschutz zu einigen? in SWR aktuell am Morgen am 13.06.2025

- Ringen um den Schutz der Meere in Spektrum am 12.06.2025

- Meere schützen oder deren Rohstoffe ausbeuten? in der FAZ am 11.06.2025

- UNO-Ozeankonferenz: Expertin ortet Gefahr von “Alleingängen” in den Salzburger Nachrichten am 11.06.2025

- Vadrot fordert klares Bekenntnis zum Meeresschutz im Ö1-Journal um acht am 10.06.2025

- Diplomaten machen blau: Was bei der UN-Ozeankonferenz auf dem Spiel steht im Standard am 09.06.2025

- UN-Ozeankonferenz 2025: Erhaltung und Wiederherstellung von marinen Ökosystemen im Science Media Center Germany am 06.06.2025