Fisheries management, Ocean Data Science, deep-sea monitoring and some of the highest level diplomats and leaders: At the United Nations Ocean Goverance (UNOC) every possible issue related to oceans and ocean governenace was discussed by the over 15.000 participants, among them also Emmanuel Macron and Ursula von der Leyen. Our TwinPolitics research team observed the conference and is giving you an overview over the most pressing issues and fault lines!

Written on site by Paul Dunshirn, Arne Langlet and Wenwen Lyu

This activity is conducted as part of the Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) under the TwinPolitics project, led by Prof. Alice Vadrot and funded by the European Research Council. In addition to UNOC3, other venues include the International Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Treaty and the International Seabed Authority.

The 3rd UN Oceans Conference (UNOC3) took place June 6-13th 2025 in Nice, France. The conference brought together over 15.000 accredited participants and 60 Heads of State and Government to exchange views on the progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 14 ‘Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development’ (SDG 14). UNOC3 was organized across a range of formal ‘blue zone’ plenaries and panels, as well as various side events, many of which were open to the public. The Ocean Science Congress, June 3rd-6th, and the Monaco Blue Economy and Finance Forum, June 7th-8th, preceded the conference.

Similar to the conference’s previous two iterations, UNOC3 did not aim to deliver formal negotiations on concrete measures or legal frameworks, as is usually the case at Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings of specific UN Treaties (Julien Rochette, IDDRI). Instead, the purpose was to bring together high-level governmental representatives and a wide diversity of ocean stakeholders (e.g., local communities, scientists, NGOs, or businesses) to discuss current political processes and forge alliances amongst ambitious actors to accomplish mutual goals. Focus lay on political processes under frameworks like the Agreement on the conservation and sustainable use of marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), or agreements related to fisheries management under the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Government representatives and non-governmental participants (at a restricted number) joined UNOC3’s Plenary to deliberate on the Nice Ocean Pact and related processes (credits: Wenwen Lyu).

Overview of UNOC3 outcomes

The formal outcome of UNOC3 is the Nice Ocean Action Plan, which included over 800 voluntary commitments and a unanimously adopted political declaration entitled “Our ocean, our future: united for urgent action”. Within and beyond the scope of these commitments, the conference’s most significant outcomes were:

BBNJ moving close to entering into force

The BBNJ Agreement is a beacon of hope for ocean conservationists and the international community. After five contentious years of negotiations (see MARIPOLDATA blog posts), the BBNJ Agreement was adopted in 2023. Since then, it has been collecting ratifications, aiming to reach the 60 ratifications required to enter into force.

By the end of UNOC3, 19 additional instruments of ratification had been deposited, and 20 more countries had signed the Agreement, signaling their intent to ratify. While this brings the number of ratifications to 50, the diplomatic efforts around UNOC3 have resulted in many countries ratifying or being quasi-ready to ratify, announcing their ratification until the UN General Assembly in September 2025. This might indicate the Treaty’s entry into force in September. Necessary groundwork for operationalizing the BBNJ Agreement is being laid during the BBNJ Preparatory Commissions in April and August 2025 and March 2026 (See Wenwen Lyu’s blog post about PrepCom 1). This includes, most importantly, setting up all subsidiary bodies to the Agreement so that when the first CoP eventually meets in 2026, BBNJ is up and running and can start its work to conserve and sustainably use the High Seas.

These developments have increased the momentum towards establishing the first generation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the High Seas. Less than 1% of the High Seas are currently protected, despite their critical role in achieving the GBF goal to protect at least 30% of Earth’s land and oceans by 2030. UNOC3 discussions have explored options for establishing such MPAs (Pew, 2024). Progress on potential MPA proposals in areas such as the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges, the Costa Rica Dome, the Gulf of Guinea, the Lord Howe Rise, and the South Tasman Sea was presented across various side events. In September 2024, Chile launched the ‘BBNJ First Movers’ initiative to support early implementation of the BBNJ Agreement by advancing proposals for first-generation High Seas MPAs.

Ongoing scientific efforts were presented across a range of blue zone events (credits: Paul Dunshirn)

Support for the deep-sea mining moratorium

Four governments (Latvia, Cyprus, Slovenia, and the Marshall Islands) joined the international coalition to precautionarily pause deep-seabed mining under the International Seabed Authority (ISA), extending the coalition to 37 countries. This was paralleled by major international banks announcing that they would not finance deep-sea mining or related activities, pledging not to enter the market for minerals stemming from deep-sea mining. US President Trump’s recent announcement to issue permits for domestic and international deep-sea mining independently of ISA negotiations only contributed to the already highly contentious character of debates on this topic.

High ambition coalition for a global plastics treaty

A significant number of 95 countries reaffirmed their high ambition coalition for the ongoing plastics negotiations during UNOC3. Initiated by the host France, the coalition published ‘The Nice wake up call for an ambitious plastics treaty ’. They demand that a global treaty to reduce plastic production and consumption should be adopted. With one round of talks remaining – scheduled from August 5 to 14 in Geneva – negotiators are now under pressure to deliver the first legally binding Treaty on plastic pollution across production, consumption, and waste.

Fisheries management

UNOC3 organizers put much focus on fisheries management, particularly on the pressing problem of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Be this through the showcasing of projects and initiatives that can monitor fishing activity and ocean spaces (through satellite data and AI) or by formal progress and commitments: the international mobilization around UNOC3 led to 14 new countries ratifying the WTO Agreement to ban subsidies to harmful fishing, bringing the number of ratifications to 103. Furthermore, 23 countries ratified the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Cape Town Agreement on safety on fishing vessels, which resulted in the Agreement’s entry into force. China ratified the FAO’s Port State Measures Agreement during UNOC3.

Blue finance

During the weekend between the One Ocean Science Congress and UNOC3, the Blue Economy & Finance Forum (BEFF) convened in Monaco, attracting 1,800 participants to explore and scale up financing for a regenerative blue economy. Addressing the severe ocean‑finance gaps, the BEFF brought together potential private and public donors to commit to financing in three waves: the 1st wave consisted of €25 billion in already identified investments in concrete ocean transition projects; the 2nd wave saw new concrete financial commitments during the BEFF amounting to €8.7 billion by 2030, which includes €4.7 billion pledged by philanthropists and private investors, and €4 billion mobilized by public financial institutions; and the 3rd wave consists of preparing the channels for continuous and sustainable ocean financing in the future. The financial commitments address sustainable maritime transport (e.g., decarbonize shipping), marine ecosystem restoration (such as coral reef and mangrove rehabilitation; see the world’s first Coral Bond in Indonesia), ocean governance and policy implementation, support for MPAs (see Blue Action Fund, which supports marine conservation by funding NGOs to protect and sustainably manage coastal and marine ecosystems in developing countries), sustainable ocean-based businesses, blue carbon projects, climate resilience, biodiversity protection, as well as de-risking mechanisms and blended finance tools to attract private capital (IISD BEFF Bulletin).

European Ocean Pact

The EU presented its Ocean Pact on June 5th, a non-legislative strategy framework for the holistic and intersectoral development of EU ocean-related policies. The Pact addresses several policy issues, ranging from the blue economy and ocean health to maritime security and defense. It endorses monitoring activities to support the realization of already existing commitments via a novel ‘ocean pact scoreboard’ and continued support for technical and scientific infrastructures. Several NGOs have welcomed the idea of an integrated approach but also questioned the Pact’s lack of concrete measures to accomplish the outlined goals. The Pact is designed to prepare a future legislative document, an EU Ocean Act, which the Commission aims to propose in 2027.

Ocean science, AI, and data under changing political circumstances

Science, AI, and data were at the forefront of UNOC3 discussions. 12 European governments renewed their commitment to jointly developing the intergovernmental institution Mercator International Centre for the Ocean during UNOC3. Mercator International already provides essential services and technologies for global monitoring efforts and synthesizes data from various (European) data and service providers, including the satellite data provider Copernicus. It also provides data access to scientific researchers, public administrations, and private companies under varying conditions.

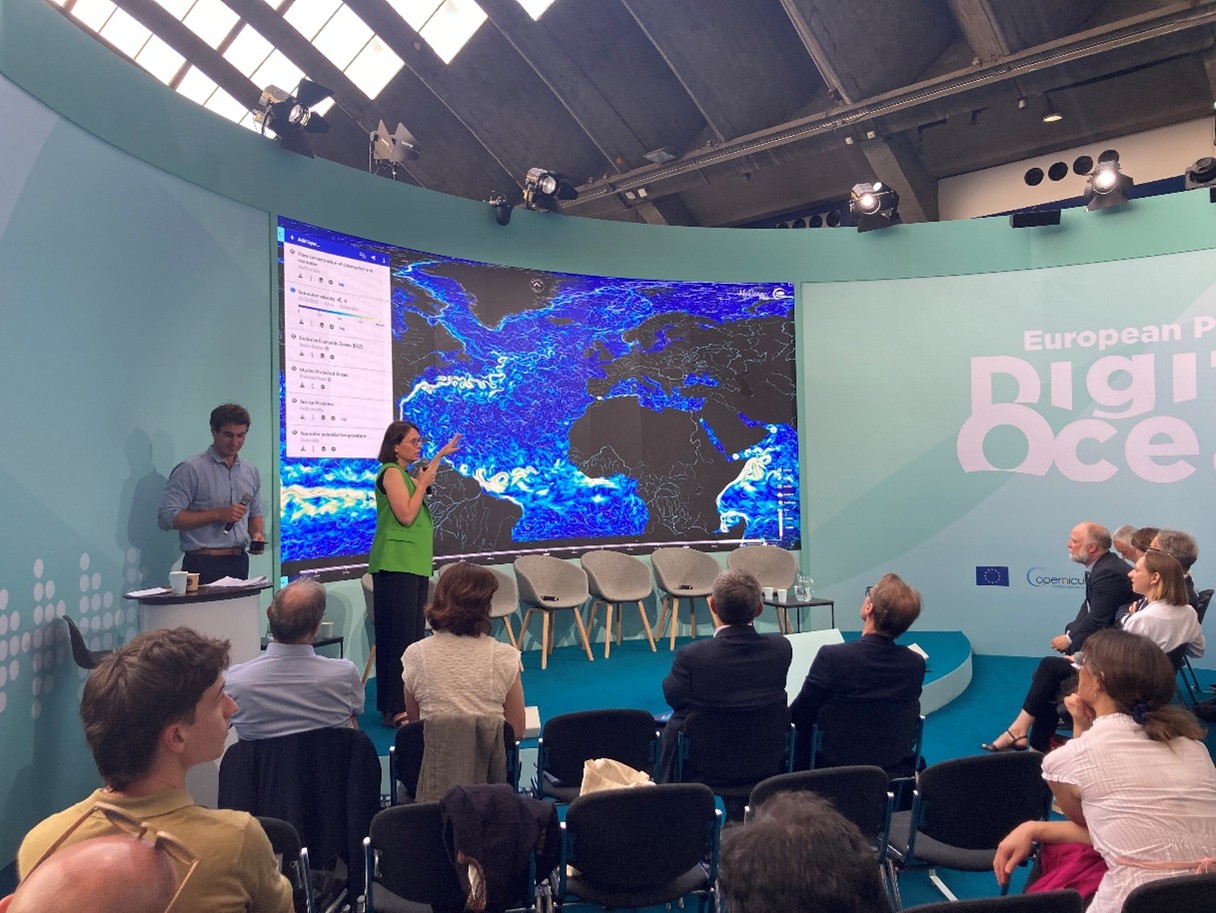

The launch of Mercator as an intergovernmental institution was connected to another major EU project called the European Digital Twin of the Ocean (EU DTO). This project’s ongoing development and implementation were displayed at UNOC3’s green zone, namely in the European Digital Ocean Pavilion. The pavilion presented an immersive and interactive exhibition showcasing the EU Digital Twin of the Ocean (DTO). It staged a full program of talks and plenaries discussing the EU’s efforts to create digital ocean representations to support political decision-making. At the same time, the China Deep Ocean Affairs Administration officially launched the Intelligent Seamount Digital Twin Systems at a UNOC3 side event, marking China’s first publicly accessible digital product in deep-sea exploration. This system also offers open access to AI models and datasets, aims to improve early warning, forecasting capabilities, deep-sea simulation, and monitoring efforts. While very successfully staging these novel technologies and presenting their value to political decision-making, these events rarely reflected on the existing geopolitical challenges linked to the wide-scale implementation of these projects (see reflections below).

European efforts to build digital ocean representations were presented at UNOC3’s green zone in the European Digital Ocean Pavilion (credits: Paul Dunshirn)

At the international level, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC-UNESCO) used UNOC3 to launch the ‘10,000 Ships for the Ocean’ initiative, aiming to enlist 10,000 commercial ships to collect and transmit vital ocean and weather data by 2035 (CRU, 2025). To date, UNESCO has equipped over 2,000 ships with scientific tools that deliver real-time information to the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS). Supported by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), France, and key actors in the shipping industry, the initiative represents a significant step in expanding global ocean observation capacity (Maritime Bell, 2025). GOOS has also expanded its Global Ocean Observing Networks to 16, including operational networks like the Argo network and emerging efforts like the deep-sea cable network. Together, these networks monitor key ocean variables such as temperature, currents, sea level, salinity, carbon, and oxygen, which are critical for understanding global ocean changes.

Reflections

Social scientific research has shown that decision-making in ocean-related political processes far exceeds the immediate setting of multilateral negotiation rooms. Various formal and informal spaces in which knowledge, politics, and people meet and interact play crucial roles in shaping governments’ positions, negotiation outcomes, and the implementation of existing agreements. UNOC3 provided exactly such a space, establishing opportunities for ocean stakeholders to network, engage in deliberation on contested political issues, and ‘stage’ their efforts and commitments publicly. Thus, while the Nice Declaration by itself will be limited in its concrete impact, the events at UNOC3 nevertheless provide crucial insights into the intentions of key institutions and political players shaping ocean governance.

UNOC3’s host countries, France and Costa Rica, adopted a strong focus on political processes around marine conservation, fisheries management, the development and application of new technologies, and blue finance. As became clear across various events, balancing fisheries and biodiversity targets continues to be a source of contention. Discussions across organizations on both sides, which took place in various UNOC3 side events, may help in finding more sustainable solutions in the face of the continuing decline in fish stocks. However, discussions between institutional representatives, NGO representatives, and scientific experts (for instance, during the brief open discussion parts at the end of official panels) displayed continued gaps between the perspectives of these stakeholders in their assessment of how fisheries and conservation can co-exist moving forward.

Additionally, the conference’s emphasis on finance addressed an often underrecognized but highly important aspect of the political process involved. Besides the new financial commitments of €8.7 billion investment by 2030, a noteworthy development was the increased recognition of ocean-related environmental risks as highly relevant to the stability of financial systems and economies at various scales. As observers (e.g., WWF; Reitmeier et al. 2024) pointed out, this particularly affects central banks, which, in recognizing these risks, can provide additional incentives and mechanisms for strengthening blue finance. European Central Bank (ECB) president Christine Lagarde’s active participation at UNOC3 should be considered a positive development in this context.

The focus on the above-mentioned topics implied less attention to others. Particularly absent were discussions related to the sharing of access and benefits derived from marine genetic resources, one of the central interests for developing countries in the BBNJ Treaty. A quick keyword search through the conference’s formal and informal programs revealed only 1 event related to marine genetic resources or research. While such ‘agenda setting’ is understandable, it needs to be noted that the successful implementation of Agreements like the BBNJ Treaty requires buy-in from all Parties. The exclusion of marine genetic resources from the conference program arguably runs counter to one of France’s major declared objectives for this conference, namely, to promote rapid entry into force and implementation of the BBNJ Treaty.

A highly relevant geopolitical dynamic shaping UNOC3 was the US government’s absence. This aligns with its recent decisions to drastically cut funding for marine scientific activities under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), but also to reduce general contributions to UN budgets. This apparent withdrawal of a central player in ocean science and conservation efforts was a central topic of concern during UNOC3. Questions over the continuation of the international Argo float program showcase this issue: Argo operates a network of around 3.600 ocean sensors providing chemical and physical data of crucial importance to central environmental monitoring services, including for the operations of EU programs like Mercator. However, the program receives over 50% of its funding from the US. Some stakeholders participating in UNOC3 have thus expressed hope that EU leaders will step in and ensure the continued operation of this network. But assurances in that regard have remained rather vague. Pascal Lamy, one of the central figures behind the EU’s efforts to expand environmental monitoring, argued at a side event organized by our team (more details will follow in our blog) that the EU indeed has an interest in investing in these infrastructures, as otherwise China will do so. This highlights how the influence and leverage to be gained through the global provisioning of such services are far from apolitical.

UNOC3 showcased the promises, challenges, and political questions of a wide range of governmental and non-governmental ocean stakeholders with respect to ongoing efforts in creating more sustainable and equitable relationships between societies and the oceans. The timely translation of announced commitments into concrete measures and critical engagement with the persisting political issues will be crucial to effectively counteract the multiple crises the oceans face. The effectiveness of these efforts will be evaluated again at UNOC4, organized by Chile in South Korea in 2028.

The Environmental Politics Research Group of the University of Vienna at UNOC3 (credits: Carolin Hirt)

Find Arne Langlet’s blog on our activities at UNOC 2025 here: Ocean Governance at a critical juncture ahead of the Third UN Ocean Conference 2025 – our participation at UNOC 2025 – Twin Politics

Find our Ocean Data Survey here: Ocean Data Survey – Twin Politics

Find other blogs on conference participation here: Blog – Twin Politics

[auf Deutsch] Unser Presse-Echo zur UNOC 2025 finden Sie hier:

- War die UN-Ozeankonferenz in Nizza für die Fisch’? im Standard am 14.06.2025

- Meeresdiplomatie: Warum ist es so schwierig, sich auf Strategien zum Meeresschutz zu einigen? in SWR aktuell am Morgen am 13.06.2025

- Ringen um den Schutz der Meere in Spektrum am 12.06.2025

- Meere schützen oder deren Rohstoffe ausbeuten? in der FAZ am 11.06.2025

- UNO-Ozeankonferenz: Expertin ortet Gefahr von “Alleingängen” in den Salzburger Nachrichten am 11.06.2025

- Vadrot fordert klares Bekenntnis zum Meeresschutz im Ö1-Journal um acht am 10.06.2025

- Diplomaten machen blau: Was bei der UN-Ozeankonferenz auf dem Spiel steht im Standard am 09.06.2025

- UN-Ozeankonferenz 2025: Erhaltung und Wiederherstellung von marinen Ökosystemen im Science Media Center Germany am 06.06.2025