As the second week kicked off, negotiations moved into more complex terrain. Meanwhile, side events brought sharper focus, opening space for more forward-looking and detailed discussions. Focusing on two major topics from the second week: the design of Subsidiary Bodies (SBs) and the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM), this blog post reflects on the data needs and position of science in the institutional design of BBNJ.

Written on site by Wenwen Lyu

This activity is conducted as part of the Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) under the TwinPolitics project, led by Prof. Alice Vadrot and funded by the European Research Council. In addition to BBNJ, other venues include the International Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Treaty and the International Seabed Authority. Lyu’s previous blog covered the first week of the negotiations.

If anything presented a stumbling block for delegates during the otherwise positive first BBNJ PrepCom, it was pronouncing the word ‘operationalization’. While it brought a sense of humour to the formal and often intense negotiations, it also served as a fitting reminder: ‘operationalizing’ the BBNJ Agreement will be anything but easy and will demand serious effort from all parties.

As the second week began (read my observations on the first week here), discussions went deeper into the design of institutional bodies, with highly technical topics such as the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM) added to the agenda. In parallel, a series of side events not only complemented but often pushed beyond the formal discussions, exploring more detailed and forward-looking issues such as the lessons learned from setting up the CHM and the Scientific and Technical Body (STB) in other multilateral processes, the market value of Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), and the synergy between BBNJ and other Multilateral Environmental Agreement (MEAs).

Across both settings, science and data were increasingly cited in states’ interventions and panel discussions, underscoring the need to consider their role within the broader political dynamics of the BBNJ institutional framework.

Co-chair Janine Coye-Felson reading the closing statement

A subtle trade-off: the influence and the risk of politicization of Subsidiary Bodies

In the second week, as discussions on the rules of procedure for the Conference of Parties (COP) (A/AC.296/2025/3) turned to the key issues of decision-making, greater divergences began to emerge in the room. One controversial point is the participation of subsidiary bodies (SBs) in the COP’s decision-making process. This discussion reflected the trade-off between empowering subsidiary bodies (SBs) to drive a science-based BBNJ process and the risk that increased influence could lead to greater politicization in a politically charged environment. (This conflict has also been highlighted by Gaebel et al.,2024 in their discussion on the design of the STB).

Discussions centred on two key questions: first, whether the Chairs of the SBs should serve as members of the COP Bureau; and second, whether they should have voting rights. On the first question, convergence emerged, with most parties agreeing that the Chairs of the SBs should not be members of the COP Bureau. The Core Latin American Group (CLAM) raised concerns that including SB Chairs in the COP Bureau would make it difficult to maintain a regional balance. Nevertheless, there was broad support for allowing SB Chairs to be invited to COP Bureau meetings to provide information and recommendations as needed.

Parties’ views on the voting rights of the SB Chairs revealed the difficult balance between enhancing the influence (of SBs) and avoiding the risk of politicization. The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) reserved its position, noting that their support would depend on whether SB members are selected in their individual or national capacity. The Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) followed a similar logic, suggesting that if chairs are selected by members serving in their individual capacity, then granting voting rights could be acceptable. These interventions reflected a shared concern: safeguards are necessary to prevent the politicization of the SBs.

Interestingly, the neutrality of the SBs was invoked by both opponents and supporters of voting rights. The African Group argued that to maintain neutrality, SB chairs should not have voting rights. By contrast, Turkey emphasized that entrusting the SBs with impartiality and allowing their chairs to vote was crucial to avoiding the disempowerment of certain delegations and ensuring equitable regional representation.

The final oral report of the Co-Chairs on the rules of procedure of the COP acknowledged the divergent views expressed regarding the voting rights of SB Chairs. This divergence highlights the inherent challenge of positioning science within a political setting. While influential SBs can support science-based governance, appropriate safeguards are necessary to address concerns about potential politicization.

Indigenous and Local Knowledge: Towards meaningful involvement

The meaningful participation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) and the integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge (ILK) were emphasized by some states and observers during discussions on the design of the SBs. The BBNJ Agreement mentions IPLCs 33 times, indicating their recognized role in ocean governance. Their inclusion in the STB similarly points to efforts of incorporating ILK into the High Seas governance framework (Fellinger & Vadrot, forthcoming). Yet, significant challenges remain in translating these commitments into concrete and operational measures.

The side event “The Scientific and Technical Body: Lessons from Other International Agreements,” organized by Pacific Small Island Developing States on 24 April, further explored this topic. Clement Mulalap, Legal Advisor of the Permanent Mission of the Federated States of Micronesia to the UN, suggested approaching it from two perspectives: the IPLC participation in the STB and parity of ILK with scientific expertise. For IPLC participation in the STB, concrete policy options to achieve these goals included nominating and electing IPLC members to the STB, allowing self-nomination to avoid political maneuvering, granting observer status, or establishing an expert panel or stand-alone advisory group.

Side event on STB

To ensure parity between ILK with scientific expertise, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) offers a valuable example. In its Global Assessment, IPBES engaged with IPLCs by appointing specific authors and formulating questions focused on ILK, integrating ILK input across all chapters, organizing dialogue workshops, and issuing calls for contributions to identify diverse knowledge systems (McElwee et al., 2020).

Clearing-House Mechanism: A data intensive package

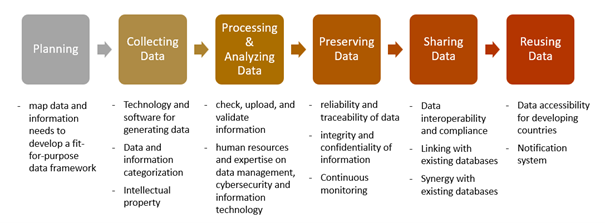

A key topic during the second week was the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM), with discussions supported by document A/AC.296/2025/6 prepared by the Secretariat. This document outlined both policy and technical considerations for the CHM’s operationalization. As a centralized platform to enable Parties to access, provide and disseminate information, data was frequently mentioned in interventions. Using the MARIPOLDATA matrix (Vadrot et al., 2024), I reviewed these interventions and categorized data-related inputs according to the stages of the Research Data Life Cycle (Ghent University Data Stewards, 2020). This method allowed for a structured analysis of how data is discussed at each stage. By revealing Parties’ expectations across the data life cycle, it offers useful insights for designing a centralized data platform—the CHM.

Combining Research Data Life Cycle with discussions on CHM

A critical reflection on the relevance of data is necessary at every stage of designing the CHM. In the current planning phase, the importance of a fit-for-purpose data framework was emphasized (see Planning Phase in the figure above). This recommendation is reflected in the way forward proposed by the co-chairs, which includes the development of a flow chart outlining the CHM’s functions. The flow chart, to be prepared ahead of the next Prep Com, will be based on the most urgent needs, enabling an incremental approach to operationalize the most important functions of CHM.

In the data collection phase, specific challenges related to the High Seas were raised. For instance, the Russian Federation highlighted the need to respect intellectual property rights, which raised broader questions about data ownership beyond national jurisdiction. Although such data is considered part of the ‘Common Heritage of Humankind’ (Vadrot et al., 2021), its governance is complicated by the involvement of diverse stakeholders, including private companies, research institutions, and individuals.

Other considerations were raised regarding the processing, preservation, sharing, and use of data. These discussions underscored the need for technical expertise in data and information management. To address these technical matters, Parties agreed to establish an open-ended expert group. Its Terms of Reference will be developed during the intersessional period and adopted at Prep Com 2.

Not reinventing the wheel: Drawing on existing CHMs

During the negotiations, many Parties emphasized the importance of ‘not reinventing the wheel’ in the establishment of the CHM. The delegate from the Philippines highlighted opportunities for international coordination, listing relevant databases under the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), the International Seabed Authority (ISA), Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), and global data infrastructures like the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Approaches to drawing on existing CHMs were explored in detail during side events.

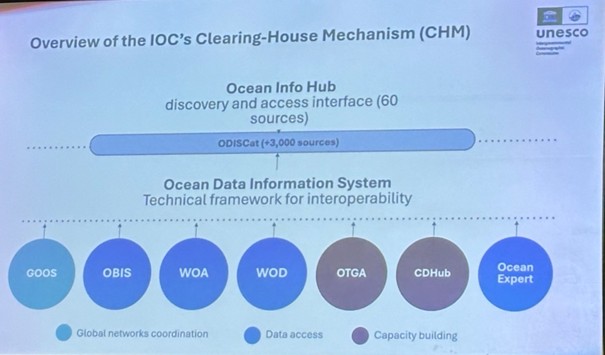

UNESCO-IOC’s Clearing-House Mechanism

On 22 April, the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO hosted the side event ‘Advancing the Design of the Clearing-House Mechanism in Support of the BBNJ Agreement’. During the event, Ward Appeltans, Manager of OBIS, explained how various databases under the IOC can support the BBNJ package elements. For example, in relation to Marine Genetic Resources (MGR), OBIS offers globally accessible marine biodiversity data, including over 9 million records from the High Seas, which can facilitate transparent and equitable access to MGR information and support the access and benefit-sharing mechanism under the BBNJ Agreement.

In a separate side event on 21 April titled ‘Synergies Between Biodiversity MEAs and the BBNJ Agreement’ and organized by the United Nations Environment Programme, Joe Appiott, Coordinator for Marine, Coastal, and Island Biodiversity at the CBD, highlighted CBD’s experience in managing three CHMs and coordinating a network of national CHMs.

During the discussions on the composition of the open-ended expert group, several Parties emphasized that expertise from the development of CHMs in other multilateral processes is essential. Technical experts will need to address a range of issues, including how to harmonize diverse data standards and formats, manage confidential or proprietary data, foster institutional cooperation across existing database custodians, and strike a balance between sophisticated data architecture and the need for user-friendly accessibility (also see MARCO-BOLO project). These are not merely technical questions but foundational challenges that will shape the functionality and legitimacy of the BBNJ CHM.

Fulfilling CHM functions: Key issues to consider

Enabling the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM) to fulfil its core functions is essential for operationalizing BBNJ package elements, including the Marine Genetic Resources (MGR), Area-Based Management Tools (ABMT) including Marine Protected Areas, Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), and Capacity Building and Technology Transfer (CBTT). For MGR, the CHM is expected to support benefit-sharing by generating BBNJ batch identifier. CHM will also serve as a platform for matching capacity-building needs. Additionally, the CHM will facilitate EIA by providing access to relevant information and support the establishment and implementation of ABMTs. To implement an incremental approach, developing countries requested to prioritize operationalizing core functions on MGR and CBTT. Side events highlighted key technical challenges associated with these functions.

One of the challenges in benefit-sharing of MGRs is determining their monetary value. On 23 April, the EU hosted a side event to present the ‘Study on MGR Market Value and the State of Commercialisation of Related Products in the Context of the BBNJ Negotiations’. The study identified two major technical obstacles to monetary benefit-sharing: first, the difficulty in verifying whether the source organism originated from the High Seas; and second, the challenge of tracking the revenues generated from MGR products. These issues will affect the selection of appropriate benefit-sharing modalities. While revenue-based or milestone payment models may capture substantial profits from successful products, they require robust tracking and monitoring system and may result in unstable funding flows. In contrast, decoupled mechanisms such as fixed annual fees offer more predictable income for the fund but may raise concerns about fairness and equity (Oldham et al., 2025).

The importance of national focal points in matching capacity-building needs was emphasized during the side event on the CHM held on 22 April. Panellists discussed the need for coordination at both national and regional levels and noted that national focal points are well positioned to identify and communicate capacity needs to the CHM. They also stressed the importance of systematic information gathering at the national level to ensure relevant input. In the IOC’s intervention, the idea of ‘creating a dynamic network comprising national and regional nodes, along with a community of practice’ was presented. The IOC has established the Ocean CD-Hub for developing country professionals to discover capacity development opportunities around the world. Given this, it is worth considering how to further develop this network to ensure continuous knowledge exchange and strengthen the community of practice.

Conclusion and Reflection

PrepCom 1 discussed the design of institutional bodies, including the Conference of the Parties (COP), the Subsidiary Bodies (SBs), the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM), and the Secretariat. Parties expressed support for the development of revised text for negotiations on the rules of procedure of the COP and preparing technical documents to clarify key issues related to the other bodies. Constructive exchanges among delegations contributed to a productive meeting, which concluded early, around 12 am on Friday.

Amid the positive and constructive atmosphere within the negotiation room, it is also important to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the scientific community and relevant institutions, frameworks, and bodies through side events held around the conference venue. These events provided practical insights and raised key considerations for the future implementation of the BBNJ Agreement. Many national delegates participated in these side events, listening to scientists, exploring complex and often forward-looking technical issues, and actively discussing important questions. This collaboration reflects the increasing need for a scientific and data-driven approach in shaping the institutional architecture of the BBNJ Agreement, as discussed at PrepCom 1.

At PrepCom 2 in August, discussions on institutional design will continue to build on the progress made during PrepCom 1 and the intersessional period. New items are added to agenda, including international cooperation, operationalization of other provisions on financial resources and mechanisms, and reporting requirements. Follow our project for continued updates as the negotiations evolve.

References:

Gaebel, C., Novo, P., Johnson, D., & Roberts, J. (2024). Institutionalising science and knowledge under the agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ): Stakeholder perspectives on a fit-for-purpose Scientific and Technical Body. Marine Policy, 161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105998

Ghent University Data Stewards (2020). Knowledge clip: The research data lifecycle. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OL_Vd9dd-AQ&t=2s

McElwee, P., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., Babai, D., Bates, P., Galvin, K., Guèze, M., Liu, J., Molnár, Z., Ngo, H. T., Reyes-García, V., Roy Chowdhury, R., Samakov, A., Shrestha, U. B., Díaz, S., & Brondízio, E. S. (2020). Working with Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) in large-scale ecological assessments: Reviewing the experience of the IPBES Global Assessment. Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(9), 1666–1676. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13705

Paul Oldham, Jasmine Kindness, Emmanuel Davidson, Amelia Westmoreland, Thomas Vanagt and Marcel Jaspars. Study on ‘Marine Genetic Resources’ Market Value and State of the Art of Commercialisation of Related Products in the Context of the BBNJ Negotiations. Publications Office of the European Union, 2025.

Vadrot, A. B. M., Langlet, A., Dunshirn, P., Fellinger, S., Ruiz-Rodríguez, S. C., & Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. (2024). Zooming in on agreement-making: Tracing the BBNJ negotiations with the MARIPOLDATAbase. Global Environmental Politics, 24(4), 152–178. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00767

Vadrot, A. B. M., Langlet, A., & Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. (2021). Who owns marine biodiversity? Contesting the world order through the ‘common heritage of humankind’ principle. Environmental Politics, 31(2), 226–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1911442